THE MAN WITH THE GOLD

Jan is developing a full-length centenary play The Man With the Gold for a run in October 2020. Four readings have taken place: at Christ's Hospital School, November 2019; at Newark Civil War Museum, 28 January 2017; at St John’s College, Oxford, 23 September 2016 and at the Cockpit Theatre, London, January 2016.

“Like the Brenton and Rattigan versions, Jan Woolf’s The Man With the Gold, uses techniques of split time, with the crucial difference that her chronology embraces the present day. This enables a kind of dialogue between then and now, from which the consequences of the past are all too starkly visible in the fractured map of the present. Much of this present is located in a museum. A custodian of memory it may be, but even this task is not performed without a degree of internal warfare. The presentation of the experts’ exhibits is a matter of such importance that they cannot achieve it without much highly entertaining, bickering, flirting and general emotional trading. Woolf literally knows her territory as she was writerin residence with the Great Arab Revolt Project (GARP), taking part in the excavation of blown up railway tracks, buttons from soldiers’ uniforms and cartridges from their guns. On the evidence of a rehearsed reading at the Cockpit Theatre, directed by Philip Wilson (Grimm Tales, at the Southbank’s Bargehouse), it speaks with power and passion about, inevitably, betrayal; not just betrayal of one person by another, or one nation by another, but of principals by their holders. Most dramatically, it conjures the person of Lawrence from the grave, giving him the chance to address us directly and debunk the myth industry which conscripted his ghost so lucratively. This is not an opportunity he can resist. Gold indeed.” Alan Franks, theatre1

‘The play is terrific: witty, unusual, and timely and it’s going to be very watchable. Bringing Lawrence to life through the preparation for an exhibition is a riveting device. You feel he is being dug out of the desert sand in front of you to rise up like a scrap of desert mist. A wraith with a message who blasts his way into the present to deliver it.’ Heathcote Williams

MEDIA

Jan contributed to a 2-hour documentary for Channel 5, Lawrence of Arabia: Britain’s Great Adventurer Available online.

Interview with Classic Times, 21 November 2018 https://www.alltimeclassic.net/jan-woolf-and-lawrence-of-arabia-in-the-defence-of-the-arab-couse/

Jan was interviewed by Radio Nottingham on 16 January 2017 about The Man With the Gold

https://soundcloud.com/richarddarn/playwright-sets-free-the-ghost-of-lawrence-of-arabia

First reading of The Man With the Gold was at the Cockpit Theatre, London, 22 January 2016. Reviewed at

http://noglory.org/index.php/events/524-jan-22-the-man-with-the-gold-cockpit-theatre

Maggie Steed and Peter Wight at Cockpit Theatre

November 2019 reading, with the scholar cast, Jan Woolf and the portrait Lawrence, Blood and Oil

Jan Woolf’s letter to the Guardian about Lawrence of Arabia and the rise of Isis, 10 April 2016:

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/10/lawrence-of-arabia-and-the-rise-of-isis?CMP=share_btn_link

Jan Woolf took part in a Radio 4 feature, aired on the PM show, Saturday 29 October 2016. Bob Walker interviewed curator Kevin Winter and archaeologist Neil Faulkner on the context of the exhibition of the Great Arab Revolt dig in Jordan – which is on show at the National Civil War Museum in Newark until spring 2017. Jan explained how participating in the dig, led to her play The Man With the Gold.

https://soundcloud.com/richarddarn/lawrence-of-arabia-bbc-radio-four

‘As a violated man, he knew the “unmooring” that violation can bring.’

Jan Woolf, the Guardian, 10 April 2016

T.E Lawrence, after Andy Warhol by Jan Woolf. Acrylic and gold painting on canvas. 4' x 3'. 2016. Used as set piece for Oxford reading 23/9/16.

Digging a play out of the desert

Autumn 2013, writer-in-residence, the Great Arab Revolt archeological dig in Jordan www.jordan1914-18archaeology.org/index.htm

I didn’t think I’d have to visit the Jordanian desert to write a play about TE Lawrence, the Arab revolt and the contemporary Middle East; but I did, and this is why.

The materiality, culture and landscape are vital in understanding this, as it shaped people and events in a way that can’t be understood from books. My play ‘The Man With the Gold’ explores the contradictions between Western expectations, political machinations and Beduin reality. Somewhere, it all reduces to economics and social consciousness – neither as romantic as the myth of Lawrence of Arabia would have it. But the complexity of Lawrence’s personality is fascinating. The ‘man with the gold’ – as the Bedu saw him – honed the ‘art’ of guerrilla warfare as still practiced today. In fact Seven Pillars of Wisdom is revered by many – from the US army to the Taliban – as a reference manual. To others it’s a sublimely written war memoir, with the contradictions of guerrilla leader and poet.

My work is being prepared for the centenary of the 1916 revolt, and set in an imaginary museum, where a major exhibition on TE Lawrence and the Arab revolt is being set up. A ghost stalks my play – a mischievous, brilliant, precocious figure, commenting on his own history and mythology as well as the current Middle East that he was central in forming. So of course I had to scrape away at layers of desert sand and rock to understand this. Archaeology and the de-layering of a personality relate in the most interesting of ways.

Desert. There is nothing here and everything here. The silence is as strong as the colour, which shifts in hues of yellow, ochre, and rust along with the position of sun. Foreground rocks are as still as the moon and the land is surprisingly soft and scabby as a result of the geo/chemical effects of acid, salt and mineral forming mosaics with crusty edges that lift scab like against yellow sand. Sometimes it looks like an elephant’s hide and exactly that colour. The critical glare of noon sun gives rocks and stones no shadow, but when shadow forms with the movement of sun it emphasises their stillness, not deadness. Apparently, before Mohammed provided a unifying religion, people worshipped sprites and spirits in rocks. I can see why.

Bits of twisted track reach into the air like burned fingers, detritus of an attack by Lawrence’s guerrilla army. I thought it an eerie place, with the imagined brutality of what happened suddenly real. The juissance of the Arabs and whatever TEL was feeling as they attacked would have got them through, not like the soldiers stuck on the train, many of them Armenian boys conscripted into the Ottoman army. I scraped at train track buried in the sand, as attentive to the beauty of the rusted and oxidised metal as I was to my troweling skills. I thought what a powerful tourist thing this would make, re-traveling the Hejaz railway from Aqaba to Medina with a son e lumiere Arab attack. What a great way to see the desert, more exciting that the Orient Express. But the attempt to rebuild the railway in the 1960s was abandoned.

Says it all really. Poor old Lawrence, they spell his name wrong and link him with fizzy drink imperialism. Tourist tread was faint because of the war in Syria and the owner of this shop was very cast down, not the time to tell him about the mis-spell.

Batn al Ghoul (place of the ghoul) for investigation of tent rings, the circles of stone used to help weight and fix tents, scraping down to find evidence and detritus of human existence; soldiers buttons, playing cards, lamp rings. There was an Ottoman encampment here in 1917 by the Hejaz railway and guarded by two hill forts. This is a stunning place, the hills behind marvelous with the overwhelming colour of sage green – despite no foliage. The colours and light are very rich, and the shimmering, miragy heat inspired stories of spirits and monsters; that you could go to sleep here and wake up with a monster or ghoul beside you – your spirit done for (there was something like this in Harry Potter). I could see how this could be an imaginative explanation for exhaustion or depression. We were working at 25 degrees C in early November and found the landscape beautiful, but at the full summer heat of 40 – 50 this landscape can shift and shimmer, a liminal space. I like this word, it means a dangerous and exciting place – outside the comfort zone. Border zones are liminal – and people can be liminal characters too, existing and traveling between two spaces. Pilgrims have a liminal phase after leaving home, when everything feels dangerous. Lawrence was a liminal character, moving between spaces and cultures.

Batn al Ghoul again. Like a beautiful face, it fascinates and can be looked at from many angles. We walked up the hill to the fortress to see some of the most wonderful landscape I’ve ever seen. The panorama of folded hills, ridges and wadis are superb, railtrack snaking through it. Apparently we are among only 200 or so people ever to have seen it. Who would go there other than beduin, archeologists, or soldiers?We were rained off here on our second day. It’s interesting what happens to the desert visually under cloud. Colours define differently. The storm rumbling around the mountains produced a spectacular atmosphere with brooding cloud and lightning flashes. The distant thunder was ‘goddish’ and I thought I could understand why the monotheist religions originated in the Middle East. But driving back we could have been in the Brecon Beacons, with the windscreen wipers going and people getting out their packed lunches.

Our day off at Petra required more energy than a day’s dig, but the excitement and poetry of the place generates plenty of adrenalin. The Nabataeans were fine artists. Walking around this vast, beautiful and complicated site of ancient civilisation in the Edom mountains was such a pleasure – coming across things like the Lion Rock.

Photographing from inside the Garden Tomb at Petra revealed the layered tiramasu (ness) of the rock. Part of the beauty here is that it hasn’t been ‘themed’ or turned into an ‘experience’ so therefore it is an – experience.

A young Bedouin man of claimed Nabotaean ancestry made a living playing his flute and running around the crag tops of the mountains in bare feet, frightening tourists. ‘Will you ever fall? I asked. Maybe, one day,’ he said, looking down the mile drop, ‘but I have such a beautiful life here. It will have been well spent.’ Nice line.

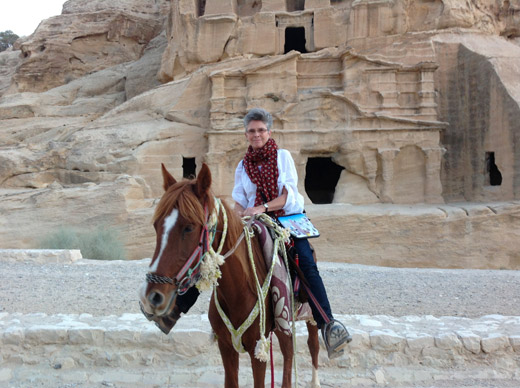

You get a free horse at Petra but most people weren’t interested, preferring the solidity of the rock under their feet – or maybe they’re scared of horses. I used my horse to ride back in the evening, with the call to prayer ricocheting off the rocks and the mountains turning pink.

Our last day on site, digging the Southern redoubt. It's lovely up there, a dramatic, panoramic view of cascading colour, rock and sand formations. But first a jeep trip deeper into the desert to the seventeenth century Haj pilgrim fort. It looked like a ruined stage set, and surreally romantic in its ice cream colours of yellow and white crenellated walls. It was used as a hospital in 1917. After treatment, Bedouin were tasked with getting surviving Turkish soldiers back home, with an IOU on delivery of a live man, otherwise they would have been killed en route as reprisal for Turkish atrocity – the vileness of war.

Sieving. Everyone else found stuff. But I found a play.

Wadi Rum. An orange and gold cavern of a place. Hard to find words that aren’t clichéd, so let’s go with majestic, wondrous, astounding. Whacking around in the back of a jeep, standing up, was mighty. The film Lawrence of Arabia was shot here and I wondered if the beauty and the cinematography was as aesthetically powerful for me as O’Toole’s face. Apparently, he would emerge from his Lebanese hotel, after a night of heavy drinking demanding ‘where the fuck’s Wadi Rum.’

A sand storm brews around Guweira rock, where Lawrence addressed the Howeitat tribes, perched on the rock like cormorants. Not quite sermon on the mount, rather a rallying for united action against the Ottomans. The art? strategy? necessity? Of guerrilla warfare. To him, the tribes were ‘a vapour’ that could win against the ‘rootedness’ of a standing army.